Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are like doors that provide access to information and functionality to other systems and applications. APIs share many of the same characteristics as doors; for example, they can be as secure and closely monitored as required.

APIs can add value to a business by allowing the business to monetize information assets, comply with new regulations, and also enable innovation by simply providing access to business capabilities previously locked in old systems.

This article is an excerpt from the book Enterprise API Management written by Luis Weir. This book explores the architectural decisions, implementation patterns, and management practices for successful enterprise APIs. In this article, we’ll define the concept of APIs and see what value APIs can add to a business.

APIs, however, are not new. In fact, the concept goes way back in time and has been present since the early days of distributed computing. However, the term as we know it today refers to a much more modern type of APIs, known as REST or web APIs.

The concept of APIs

Modern APIs started to gain real popularity when, in the same year of their inception, eBay launched its first public API as part of its eBay Developers Program. eBay’s view was that by making the most of its website functionality and information also accessible via a public API, it would not only attract, but also encourage communities of developers worldwide to innovate by creating solutions using the API. From a business perspective, this meant that eBay became a platform for developers to innovate on and, in turn, eBay would benefit from having new users that perhaps it couldn’t have reached before.

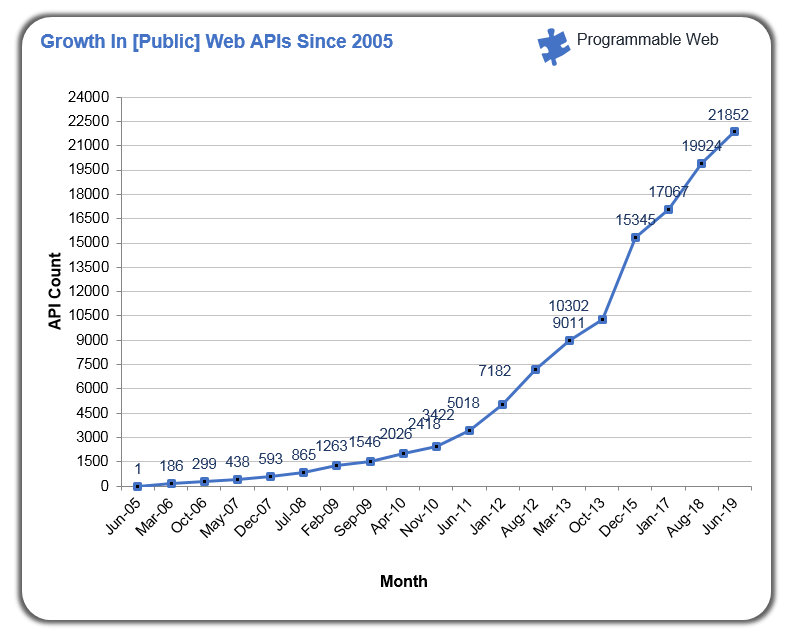

eBay was not wrong. In the years that followed, thousands of organizations worldwide, including known brands, such as Salesforce.com, Google, Twitter, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and many others, adopted similar strategies. In fact, according to the programmableweb.com (a well-known public API catalogue), the number of publicly available APIs has been growing exponentially, reaching over 20k as of August 2018.

Figure 1: Public APIs as listed in programmableweb.com in August 2018

It may not sound like much, but considering that each of the listed APIs represents a door to an organization’s digital offerings, we’re talking about thousands of organizations worldwide that have already opened their doors to new digital ecosystems, where APIs have become the product these organizations sell and developers have become the buyers of them.

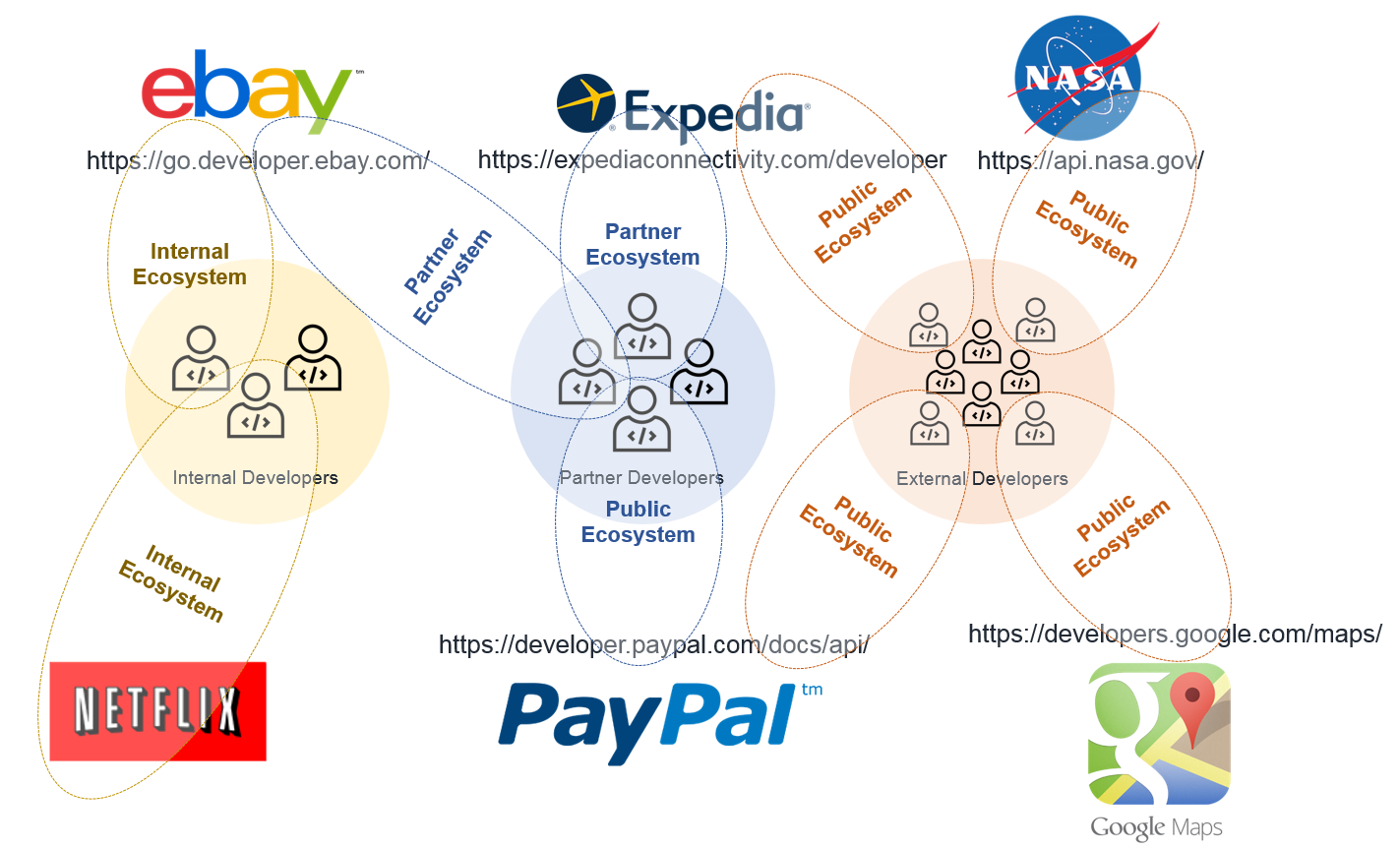

Figure: Digital ecosystems enabled by APIs

In such digital ecosystems, communities of internal, partner, or external developers can rapidly innovate by simply consuming these APIs to do all sorts of things: from offering hotel/flight booking services by using the Expedia API, to providing educational solutions that make sense of the space data available through the NASA API.

There are ecosystems where business partners can easily engage in business-to-business transactions, either to resell goods or purchase them, electronically and without having to spend on Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) infrastructure. Ecosystems where an organization’s internal digital teams can easily innovate as key enterprise information assets are already accessible.

So, why should businesses care about all this? There is, in fact, not one answer but multiple, as described in the subsequent sections.

APIs as enablers for innovation and bimodal IT

What is innovation? According to a common definition, innovation is the process of translating an idea or invention into a good or service that creates value or for which customers will pay. In the context of businesses, according to an article by HBR, innovation manifests itself in two ways:

- Disruptive innovation: Described as the process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses.

- Sustaining innovation: When established businesses (incumbents) improve their goods and services in the eyes of existing customers. These improvements can be incremental advances or major breakthroughs, but they all enable firms to sell more products to their most profitable customers.

Why is this relevant? It is well known that established businesses struggle with disruptive innovation. The Netflix vs Blockbuster example reminds us of this fact. By the time disruptors are able to catch up with an incumbent’s portfolio of goods and services, they are able to do so with lower prices, better business models, lower operation costs, and far more agility, and speed to introduce new or enhanced features. At this point, sustaining innovation is not good enough to respond to the challenge.

With all the recent advances in technology and the internet, the rate at which disruptive innovation is challenging incumbents has only grown exponentially. Therefore, in order for established businesses to endure the challenge put upon them, they must somehow also become disruptors. The same HBR article describes a point of view on how to achieve this from a business standpoint. From a technology standpoint, however, unless the several systems that underpin a business are “enabled” to deliver such disruption, no matter what is done from a business standpoint, this exercise will likely fail.

Perhaps by mere coincidence, or by true acknowledgment of the aforesaid, Gartner introduced the concept of bimodal IT in December 2013, and this concept is now mainstream.

Gartner defined bimodal IT as the following:

“The practice of managing two separate, coherent modes of IT delivery, one focused on stability and the other on agility. Mode 1 is traditional and sequential, emphasizing safety and accuracy. Mode 2 is exploratory and nonlinear, emphasizing agility and speed.”

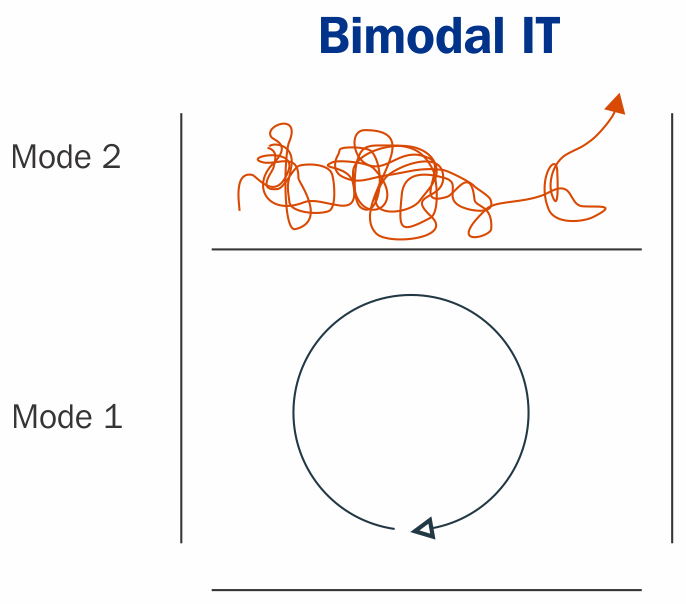

Figure: Gartner’s bimodal IT

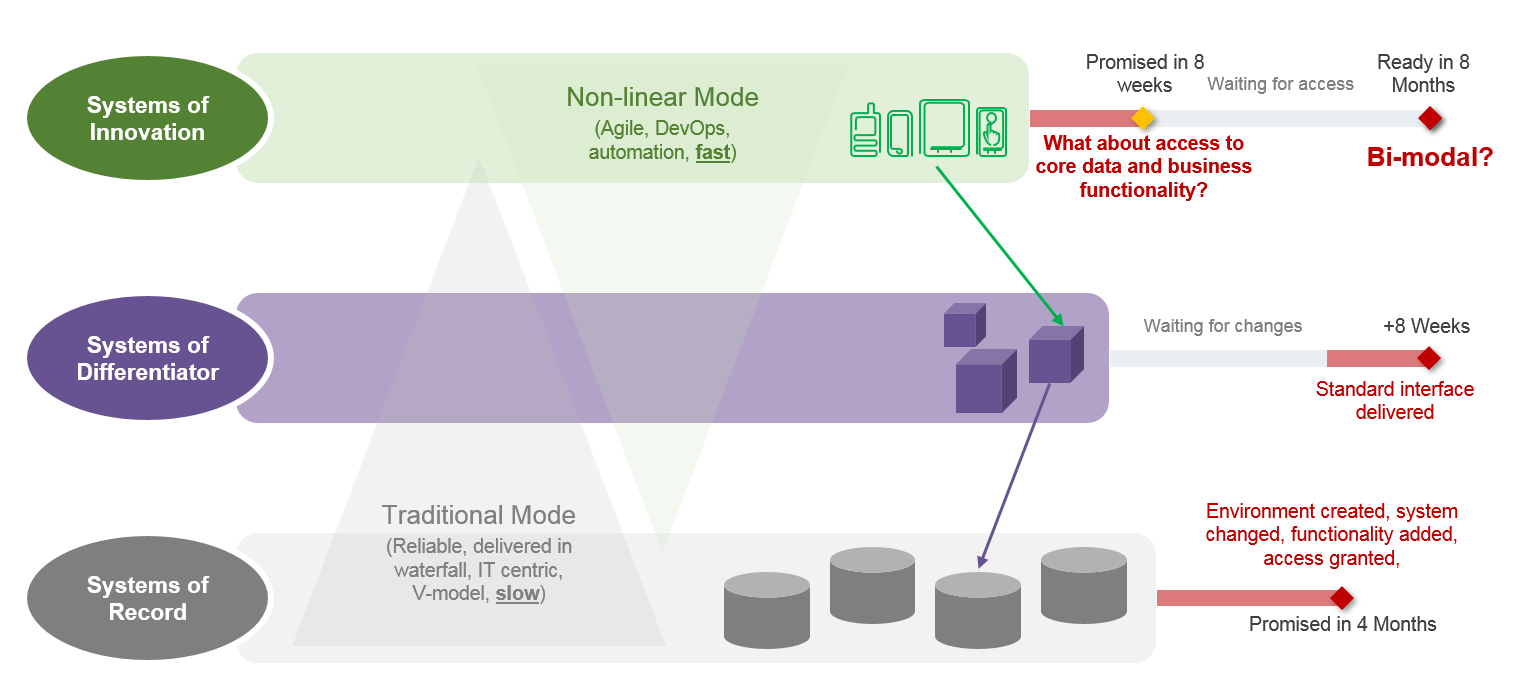

According to Gartner, Mode 1 (or slow) IT organizations focus on delivering core IT services on top of more traditional and hard-to-change systems of record, which in principle are changed and improved in longer cycles, and are usually managed with long-term waterfall project mechanisms. Whereas for Mode 2 (or fast) IT organizations, the main focus is to deliver agility and speed, and therefore they act more like a startup (or digital disruptor in HBR terms) inside the same enterprise.

However, what is often misunderstood is how fast IT organizations can disruptively innovate, when most of the information assets, which are critical to bringing context to any innovation, reside in backend systems, and any sort of access has to be delivered by the slowest IT sibling. This dilemma means that the speed of innovation is constrained to the speed by which the relevant access to core information assets can be delivered.

As the saying goes, “Where there’s a will there’s a way.” APIs could be implemented as the means for the fast IT to access core information assets and functionality, without the intervention of the slow IT. By using APIs to decouple the fast IT from the slow IT, innovation can occur more easily.

However, as with everything, it is easier said than done. In order to achieve such organizational decoupling using APIs, organizations should first build an understanding about what information assets and business capabilities are to be exposed as APIs, so fast IT can consume them as required. This understanding must also articulate the priorities of when different assets are required and by whom, so the creation of APIs can be properly planned for and delivered.

Luckily for those organizations that already have mature service-oriented architectures (SOA), some of this work will probably already be in place. For organizations without such luck, this activity should be planned for and should be a fundamental component of the digital strategy.

Then the remaining question would be: which team is responsible for defining and implementing such APIs; the fast IT or slow IT? Although the long answer to this question is addressed throughout the different chapters of this book, the short answer is neither and both. It requires a multi-disciplinary team of people, with the right technology capabilities available to them, so they can incrementally API-enable the existing technology landscape, based on business-driven priorities.

APIs to monetize on information assets

Many experts in the industry concur that an organization’s most important asset is its information. In fact, a recent study by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) suggests that data is the single most important asset for organizations

“Data is now a form of capital, on the same level as financial capital in terms of generating new digital products and services. This development has implications for every company’s competitive strategy, as well as for the computing architecture that supports it.”

If APIs act as doors to such assets, then APIs also provide businesses with an opportunity to monetize them. In fact, some organizations are already doing so. According to another article by HBR, 50% of the revenue that Salesforce.com generates comes from APIs, while eBay generates about 60% of its revenue through its API. This is perhaps not such a huge surprise, given that both of these organizations were pioneers of the API economy.

Figure: The API economy in numbers

What’s even more surprising is the case of Expedia. According to the same article, 90% of Expedia’s revenue is generated via APIs. This is really interesting, as it basically means that Expedia’s main business is to indirectly sell electronic travel services via its public API.

However, it’s not all that easy. According to the previous study by MIT, most of the CEOs for Fortune 500 companies don’t yet fully acknowledge the value of APIs. An intrinsic reason for this could be the lack of understanding and visibility over how data is currently being (or not being) used. Assets that sit hidden on systems of record, only being accessed via traditional integration platforms, will not, in most cases, give insight to the business on how information is being used, and the business value it adds. APIs, on the other hand, are better suited to providing insight about how/by whom/when/why information is being accessed, therefore giving the business the ability to make better use of information to, for example, determine which assets have better capital potential.

In this article we provided a short description of APIs, and how they act as an enabler to digital strategies. Define the right organisation model for business-driven APIs with Luis Weir’s upcoming release Enterprise API Management.

Read Next

To create effective API documentation, know how developers use it, says ACM

![How to create sales analysis app in Qlik Sense using DAR method [Tutorial] Financial and Technical Data Analysis Graph Showing Search Findings](https://hub.packtpub.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/iStock-877278574-218x150.jpg)