Networking attacks in blockchain are mostly ignored due to the difficulty involved in defeating a decentralized network that works using the peer-to-peer protocol. This doesn’t mean that attacks on peer-to-peer networks are impossible. In this article, we’ll be discussing one of the network attacks known as eclipse attacks.

This article is an excerpt from the book, Foundations of Blockchain by Koshik Raj. Blockchain technology is a combination of three popular concepts: cryptography, peer-to-peer networking, and game theory. Foundations of Blockchain is for anyone who wants to dive into blockchain from first principles and learn how decentralized applications and cryptocurrencies really work.

In an eclipse attack, the attacker eclipses the node from the network. The attacker makes sure that the node will not communicate with the blockchain network. The node will believe in a completely different truth than the rest of the network after the node is compromised by the attack. Generally, eclipse attacks are performed on high-profile blockchain nodes such as miners or merchants.

The eclipse attack was proposed by computer security researchers Ethan Heilman, Alison Kendler, Aviv Zohar, and Sharon Goldberg in 2015. They published a Usenix Security paper titled Eclipse Attacks on Bitcoin’s Peer-to-Peer Network. The paper explains the possibility of an attack on Bitcoin’s peer-to-peer network. Although the attack is mainly focused on Bitcoin, it can be performed on the peer-to-peer networks of another blockchain platform as well. Another paper, titled Low-Resource Eclipse Attacks on Ethereum’s Peer-to-Peer Network, which was published in 2018, analyzed the feasibility of an eclipse attack in the Ethereum network. We will look into the details of eclipse attacks based on the first of these papers.

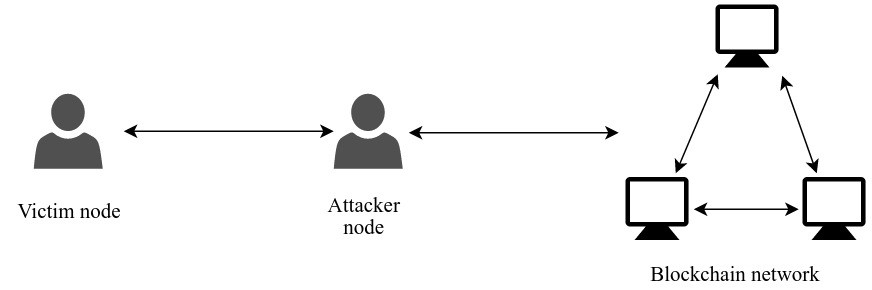

In a blockchain network, peers use a gossip protocol to set up an initial connection and exchange information. Each node learns about the peers in the network from the connected nodes. In an eclipse attack, the attacker prevents the victim from learning about the rest of the network by not gossiping about the other nodes. The attacker node is directly connected to the victim node, as shown in Figure 1. The attack looks similar to the man-in-the-middle attack performed between the client and the server in a centralized network. We will assume that attack takes place in Bitcoin’s Proof of Work ecosystem to understand and analyze the eclipse attack in the coming sections.

Figure.1: The position of the attacker in an eclipse attack

Eclipsing the node

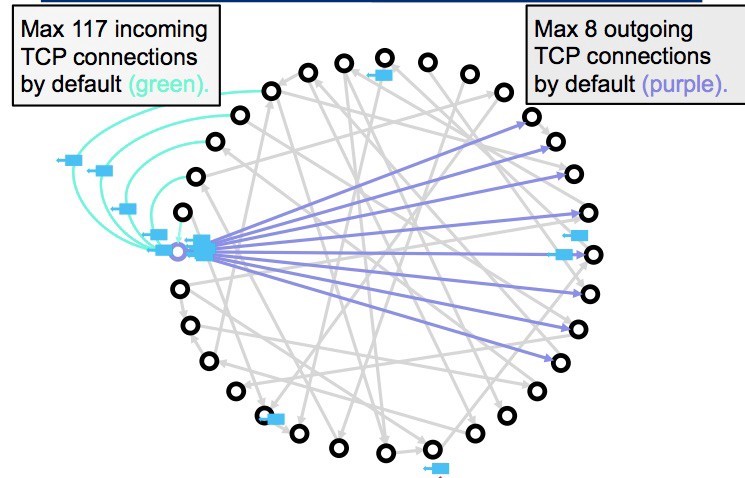

A Bitcoin node can have a maximum of 8 outgoing and 117 incoming connections. Since there’s a limit on the number of outgoing connections, the attacker can force the victim to solely establish connections to malicious nodes created by the attacker:

Figure.2: Bitcoin node with outgoing and incoming connections in a peer-to-peer network

This may look easy in theory; however, forcing the victim to only create connections to malicious nodes requires more than a single step attack. The attacker has to learn and manipulate the victim’s connection information to manipulate the user’s outgoing connections. Bitcoin nodes store outgoing connection information in a peer table. The peer table is organized into buckets of addresses. Filling these buckets with the attacker’s IP addresses is the idea behind the attack. An attacker will use several vulnerabilities in Bitcoin Core to achieve this. Once the peer table is filled with the attacker’s node information, the victim will only attempt to connect to the attacker’s nodes after the node has been rebooted.

Implications and analysis of the Eclipse attack

Blockchain applications revolve around the principle of decentralization. Decentralization is achieved with the help of equally responsible nodes that are connected to form a peer-to-peer network. It’s essential for most of the blockchain nodes (if not all) to exhibit similar functionality to achieve a purely decentralized network. This can be a challenging task because there is no authority in the public network to enforce rigid rules on the functionality of nodes. Many blockchain networks are being forced to centralize to improve the performance or integrate with the existing centralized entities. This exposes decentralized systems to potential issues that are already faced by existing centralized systems. We’ll discuss some of the entities that have caused centralization and exposed decentralized networks to some of the potential threats.

To gain more insight into the security issues that exchanges have been the victims of attacks due to centralization, let’s go over three high profile examples.

In August 2016, around 1,20,000 bitcoins were stolen from Bitfinex wallets. Bitfinex reduced the bitcoin funds of all their customers by 36%, including the customers whose wallets were not compromised. Newly minted BFX tokens were deposited in customers’ accounts in proportion to their losses. Since these tokens did not have any intrinsic value in any other exchanges, they promised to buy back these distributed tokens eventually.

Bitcoin has two different set of buckets that store peer information: a set of new buckets and a set of tried buckets. New buckets consist of addresses of newly available peers, whereas tried buckets store addresses of already-connected peers. When a node first connects to a peer, it adds the peer’s information, along with a timestamp, to the tried bucket. The connected peer passes known peer information to the node, and the node stores this in the new bucket. When the node connects to the attacker’s device, it will send information about the malicious peers so that the node stores those addresses in the new bucket.

When a new connection is successfully made by the node, it will add the IP address to one of the 256 tried buckets. It randomly selects a single bucket but randomizes the selection based on the network ID and the full IP address. This is also the same in the case of adding IP addresses to the new bucket. Various vulnerabilities of the Bitcoin node can be exploited to make sure that most of the addresses in the bucket are the attacker’s addresses. Several vulnerabilities of the Bitcoin node are pointed out in Vulnerabilities and countermeasures section.

Since the eclipse attack is performed on the network layer, it can break the security of the consensus layer too. Any attack on the consensus layer can be more effective when the node’s peer-to-peer protocol is compromised. A 51 percent attack without the attacker owning the majority of the computing power, or the double-spend attack even after several block confirmations, can both be performed when an eclipse attack is performed.

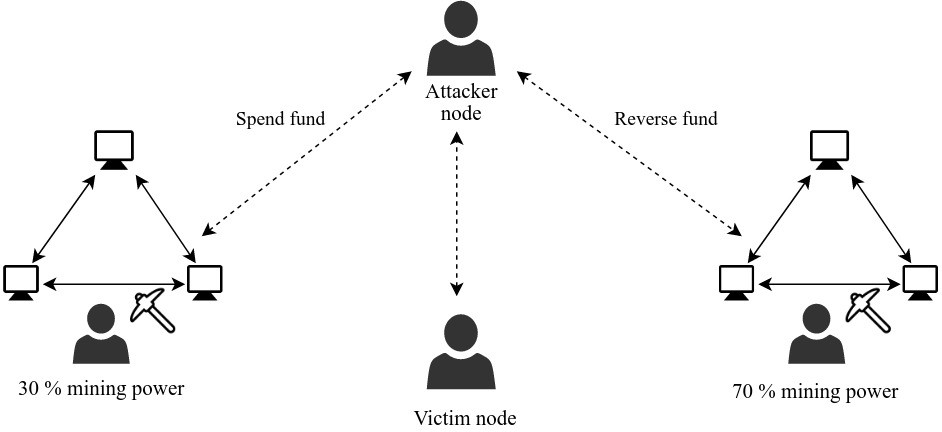

An attacker can double spend a transaction even after n-confirmation simply by eclipsing a fraction of miners and the victim node. The attacker can spend a fund and forward it to the eclipsed miner. When the miner includes this in a block, the attacker shows this blockchain to the victim node. The victim is convinced after looking at the confirmed transaction. The attacker also forwards a transaction to double spend the same fund. When the attacker completes their purchase from the victim, they reveal the actual blockchain to both the eclipsed miner and the victim, thus making their blockchain obsolete.

A double-spend attack is performed in Figure 3. The attacker eclipses a miner who controls 30 percent of the mining power and the victim. The attacker spends a fund and sends the transaction to the eclipsed miner. The eclipsed victim only views this version of the blockchain. The attacker then spends the same fund and creates a transaction that is viewed by the rest of the network. Since this network controls the majority (70 percent) of the mining power, it will create a longer blockchain, making the eclipsed miner’s blockchain obsolete:

Figure.3: Double-spend attack by eclipsing the victim node

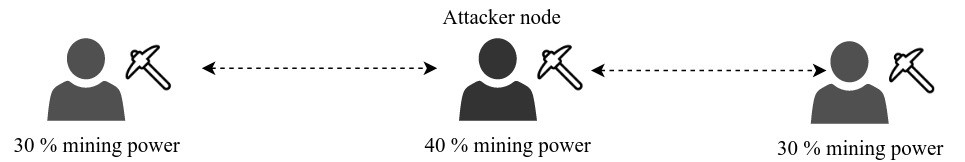

If an attacker is a miner, he can launch a 51 percent attack without owning 51 percent of the computing power of the network. This can be achieved by preventing the honest miners from controlling the majority of the computing power. The attacker can eclipse a few miners from rest of the network, which would prevent miners from building blocks on each other’s created blocks. This will prevent honest miners from owning the majority of the power to create blocks. This will increase the chances of an attacker with less than 51 percent of the mining power launching a 51 percent attack. Figure 4 shows that an attacker with 40 percent of the mining power eclipses two miners, each controlling only 30 percent of the mining power in the network.

Now that attacker owns the majority of the mining power; they have a better chance of ending up with a longer chain than the other miners who are isolated from each other. Each miner who is unaware of the rest of the network will keep building their own version of the blockchain. The attacker can publish their blockchain to the network at any time, making other versions of the blockchain obsolete.

Figure.4: 51 percent attack with less than 50 percent of mining power

Although the eclipse attack may seem unrealistic, it isn’t actually. A clever attack with the help of botnets can easily compromise a node that doesn’t implement an additional layer of network security. The published paper Eclipse Attacks on Bitcoin’s Peer-to-Peer Network explains the chances of an eclipse attack occurring with different scenarios. An experiment performed with botnets produced the following results:

- A worst-case scenario was created by filling tried bucket slots with addresses of honest nodes. An attack was performed with a total of 4,600 IP addresses for a period of 5 hours. Although the tried bucket slots were initially mostly filled with the addresses of honest nodes, 98.8 percent of them were replaced with the attacker’s addresses after the attack. The attack had a 100 percent success rate.

- An attack was performed on live Bitcoin nodes that had only 7 percent of the tried address slots filled with legitimate addresses. The attack was simulated by attacking with 400 IP addresses and only 1 hour invested in the attack. The tried table was filled with around 57 percent of attacker addresses after the attack. This attack had a success rate of 84 percent.

Vulnerabilities and countermeasures

The attacker has to exploit a few vulnerabilities to replace legitimate peer addresses with their own addresses. Some of the vulnerabilities in Bitcoin nodes that can be exploited are as follows:

- The node selects the IP addresses from the tried bucket with recent time stamps, which increases the probability of the attacker getting selected even if the attacker owns a small portion of the tried bucket addresses. The attacker can increase the chances by increasing the attack time.

- Whenever an address bucket is filled, one of the addresses is removed randomly. Since the removed address is random, if an attacker’s IP is removed from the bucket, it can be eventually inserted by repeatedly sending it to the node.

The attacker can exploit these mentioned vulnerabilities. However, these vulnerabilities can be avoided by altering the behavior of the Bitcoin node while gossiping with the peers:

- Selection of the IP address from the tried table could be randomized, which would reduce the chances of selecting an attacker peer even if it was recently connected. The attacker will not be successful even after investing a lot of time in the attack if peer selection is randomized.

- If a deterministic approach is used to insert the address of the peer into a fixed slot, it will reduce the chances of inserting the attacker’s address to a different slot after it is evicted from the bucket. Deterministic insertion will ensure that repeated insertion of addresses will not add any value to an attack.

Most of the vulnerabilities in Bitcoin have been fixed. But due to the public blockchain networks and open source culture followed by most blockchain-based organizations, attackers will quickly find vulnerabilities.

In this article, the theory behind eclipse attacks was discussed. The various ways in which it could compromise Bitcoin networks were, the vulnerabilities and the countermeasures to alleviate bitcoin network are listed.

Learn basic blockchain concepts and algorithms in Python from our latest book Foundations of Blockchain written by Koshik Raj.

Koshik Raj is an information security enthusiast who holds a master’s degree in computer science and information security. He has a background of working with RSA, a network security company. He has also worked as a senior developer in CoWrks, Bengaluru.

Read Next

Understanding the cost of a cybersecurity attack: The losses organizations face

Knowing the threat actors behind a cyber attack

200+ Bitcoins stolen from Electrum wallet in an ongoing phishing attack

![How to create sales analysis app in Qlik Sense using DAR method [Tutorial] Financial and Technical Data Analysis Graph Showing Search Findings](https://hub.packtpub.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/iStock-877278574-218x150.jpg)